A Remarkable Ego

Here's a book review I did for the Spring 2009 issue of The Great Plains Newsletter. This post is way too long, according to the blog gurus, but to hell with them. The newsletter isn't available online, so thought I'd offer it here.

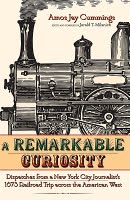

Here's a book review I did for the Spring 2009 issue of The Great Plains Newsletter. This post is way too long, according to the blog gurus, but to hell with them. The newsletter isn't available online, so thought I'd offer it here.A Remarkable Curiosity: Dispatches from a New York City Journalist's 1873 Railroad Trip Across the American West. Edited and compiled by Jerald T. Milanich. Boulder: The UP of Colorado, 2008, 371 pages, with index and illustrations.

Although few have heard of him now, Amos Jay Cummings was once the most popular journalist in the United States. More than a hundred years after his death, dispatches from his 1873 railway journey across the American west have been collected by anthropologist Jerald T. Milanich.

Milanich, curator of archaeology at the Florida Museumof Natural History at Gainesville, became interested in Cummings when he read an unsigned newspaper account of a visit to Turtle Mound, a huge shell heap left by ancient Indians on the Atlantic coast. Intrigued, Malevich found phraseology similar to the Turtle Mound article in an 1875 guidebook to Florida that was authored by “Ziska,” an obvious pseudonym.

After what Malevich describes as a “wild literary adventure,” he confirmed that Ziska was in fact Amos J. Cummings – journalist, Civil War hero, and Congressman.

And, one might add, liar and shameless self-promoter.

Cummings was born in 1838 in a small town near border between Pennsylvania and New York. He claimed to have run away at 15 to become an “itinerant typesetter,” although this is certainly an exaggeration, a stretcher told by Cummings in his later years to make his life seem more romantic. He also claimed to have accompanied William Walker during the 1858 invasion of Nicaragua, but Malevich is rightly suspicious – neither the dates nor the details add up to allow Cummings to have been with Walker during any of his ill-fated attempts to establish a slave-holding Southern empire in Latin America.

During the Civil War, Cummings was a volunteer with a New Jersey infantry regiment, and saw action at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Thirty years after the war – and following his election to Congress – he received the Medal of Honor for leading a charge to save a Union gun from falling into rebel hands during the battle of Salem Church on May 4, 1863.

Milanich concludes that Cummings was a “bona fide war hero” because about a third of the 35 New Jersey soldiers who were awarded the medal got theirs long after the war, too. But the most complete account of the feat of heroism that saved the cannon appears to have penned by – you guessed it – Cummings himself.

“One thing I soon learned,” Milanich writes in a classic bit of understatement, “was that Cummings and his biographers did not always provide correct or truthful information.”

The stretchers include moving his year of birth to 1841, apparently to make Cummings appear younger. The reason, Milanich, believes, was vanity. After his success as a travel writer sending back anonymous dispatches from wild and wooly Florida, Cummings (who was managing editor of The New York Sun) undertook the six-month railway journey to the west. It was during this journey that he began filing his dispatches under Ziska.

Alas, Milanich never discovered why Cummings chose the odd pseudonym.

“I’ve been trying to figure it out since I first discovered that Ziska was Cummings,” Milanich said in an email message. “Had I been a reasonably literate person in 1873 I probably would know immediately, but.. . .”

While such affected journalistic handles were common during the period, Ziska no longer rings like the pen name of one of his travel writing contemporaries, Mark Twain. His prose pales in comparison as well, which may be much of the reason Cummings is forgotten and Twain is not. To say that his style is dry is like saying that rain is wet.

“The trip by railroad over the plains is monotonous,” Cummings reports from Kansas. “It is generally understood that passengers have not a thing to do during the journey but to gaze at immense buffalo herds and shoot antelopes.

Although it was in the buffalo season, I saw none of the animals.”

Still, there is much historical value in his accounts. The best example may be an interview Cummings did in July 1873 at Salt Lake City with Brigham Young. The 78-year-old patriarch was being sued for divorce and $200,000 by his seventeenth wife, Ann Eliza.

“I had a talk with the Mormon Prophet yesterday,” Cummings begins, and goes on to provide a detailed account of his reception: “I saw the great Religious Chief sitting on a sofa before I entered the room. I recognized him from the pictures that I had seen hanging at the doors of the Salt Lake photograph galleries. He was looking toward the stoop, and evidently expecting me. He kept his eyes fixed upon me as I approached, then he arose, shook hands, politely offered me his seat upon the sofa, and sat down upon a chair at my side.”

A sort of transcript follows, and when Cummings asks about the divorce suit, Young explodes.

“Blackmail! Blackmail! It is not the first time they have attempted to Blackmail the Mormon Church, and I presume it will not be the last. We have never allowed them to blackmail us out of a single cent, and we don’t propose to allow them to do so now.”

A day later, he interviewed Ann Eliza Young. During the long session, he asked the 30-year-old woman why she thought Young had acquired so many wives.

“Well, we (meaning she and the other wives) think it’s vanity. He just wants to show that if he is an old man he can marry young women; and he isn’t the only one in power who does the same thing.”

About a third of the dispatches are devoted to the divorce and other Mormon issues, apparently to feed the growing American fascination with the polygamous desert sect. The remaining articles are mostly sketches of the colorful characters that Cummings met on his curious journey to San Francisco. In one, he describes a winter storm from the point of view of a rancher along Gypsum Creek in central Kansas:

“A night’s ride in a hard norther, fifty vain endeavors to get the cattle turned against the wind, and then daylight. You find you are on the banks of the Arkansas River, and have lost some twenty or thirty animals. You are cold, frost bitten, hungry, and want to sit down and die. That is Kansas winter.”

Before Cummings left San Francisco on Nov. 4, 1873, he wrote the article that would appear in The San Francisco Chronicle announcing his departure. In it, he describes himself as “an accomplished angler as well as a brilliant and vivacious writer.”

While Cummings makes a modern journalist uncomfortable with his megalomania and casual grip on the truth, his contribution to reporting – and to history – is undeniable. Milanich has rightly restored Cummings to public consumption. He plans a follow-up volume, one dealing with Cummings and his connection to Thomas Edison – it was Cummings, through his pieces in The New York Sun, that first brought the inventor to national attention, when Edison was searching for a suitably durable filament during the invention of the light bulb.

<< Home